Dr. Errold D. Collymore, Sr. - D.D.S.

(1892-1972)

.jpg)

Introduction

Since 1986, we in the United States celebrate the birthday, life, and legacy of Dr, Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929-1968). His work and achievements in advancing the cause of justice and civil rights for colored/negro/black/African-American people within the United States is a bright star in American history.

It should not, must not, be forgotten though, that for every figure canonized in the national psyche, there are always those that came before, or that worked in the shadows, to bring about changes on a smaller scale, by which the great changes may not have been made possible or been pursued. The work of such people is often forgotten, ignored, or unappreciated by later generations.

It is my wish here to make a small effort to ensure that does not happen to one such man who also worked to secure the civil rights of African-Americans. A man who had to work his way to the United States as an immigrant from the Caribbean; yet, who embraced and held dear the principles of what America stood for, and who turned much of his energies to making a better life not just for himself, but for others who suffered the injustices of racism in one small region of the northeastern United States. This man, who happened to be, my father.

A brief history

Dr. Errold D. Collymore, Sr., D.D.S., was born in Barbados, B.W.I. in 1892. He was one of five children. Two of his siblings died in infancy.

During his lifetime, he worked very hard to attain the things he valued.

When his mother lost her clerical/secretarial job at a sugar plantation in Barbados, he worked his way to the U.S. from Barbados by way of the Panama Canal (when it was being built!). While there, he learned Morse Code and became a radio (a.k.a., "Ham") operator for the office overseeing the building of the canal. Accumulating the money to get himself, and later his mother and two brothers, from Panama to the United States took a while since he, like other blacks working on the canal, was paid a lower wage than whites. During these segregated times, black workers were paid on what the construction company called: the "Silver Standard." This meant that they were paid their wage only in silver coin. Whites, on the other hand, were paid higher wages, and their's was called the "Gold Standard." Meaning, they were to be paid enough to merit that gold coins would make up their pay.

Working on the canal did provide an added bonus though, my father learned to speak fluent Spanish.

After several years, he was finally able to afford a steam ship ticket to the U.S. He came through Ellis Island. At this time, World War I was raging and, wanting to gain a "fast track" to U.S. citizenship, he enlisted in the U.S. Army. Because of the radio skills he'd acquired working on the Panama Canal, he became a radio operator in the Army.

He was eventually able to earn enough money to send for his older brother, Archibald, to come to the U.S. Eventually, the two of them earned enough money to send for their mother, Louisa, and their younger brother, Walter, to join them.

Knowing that the doorway to a good future was through a good education, my father soon began looking at universities that he might attend. Unfortunately, he was limited in his choices since many colleges were either segregated or too expensive. Wanting to become a medical doctor (M.D.), my father applied to one of the few black universities on the east coast with a medical school, Howard University.

Unfortunately, things for a foreigh-born black man were not that easy even going to a black university, especially since my father was now older than the typical age for admission to college. One of the administrators at Howard stated that to gain admission my father would have to get scores of 90 and above (out of 100) in exams in five subjects: mathematics, English, history, science, and Latin. My father exceeded 90 in all five of the exams and was admitted to Howard.

By the time my father was ready to enter Howard, he realized that because he was starting school so late in life (and because he wanted to begin earning a living) that the shorter, dentistry, program would be a wiser choice. He graduated with a Doctor of Dental Surgery (D.D.S.) and established his first practice in New York City.

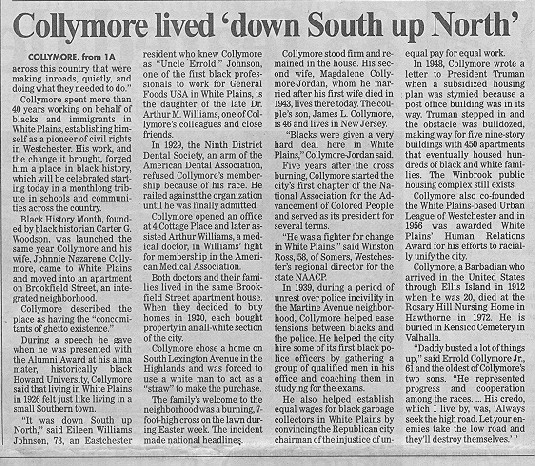

Eventually, he was able to afford a house in White Plains, NY, in a new, upscale development called: "The Highlands." But this home would not be obtained without first facing some of the worst, and most public, examples of American racism that a black man could experience. Not the least of which was the burning of a six-foot cross on the front lawn of his new home in the spring of 1930.

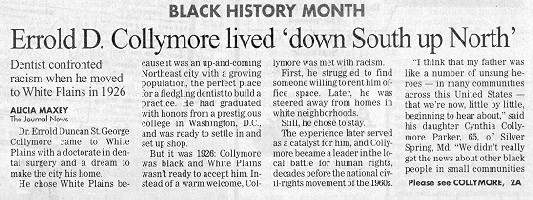

The articles that follow (reprinted with permission) describe some of what happened when he tried crossing the "color line." If you think that what happened in the deep South during the 1920's & 1930's couldn't happen up in the suburbs of Northern states, well, read on.

Articles

Another article gives some more interesting details about the cross-burning.

Accomplishments

During his lifetime, Dr. Collymore has been recognized for a number of his civil rights achievements in the lower Hudson River valley of New York State. Most of these occured during the 1930's-1950's, long before civil rights was a "popular" cause in the United States.

Some of these include:

- Founding the first chapter of the White Plains-Greenburgh National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1935.

- Serving as President of the White Plains Colored Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA). (Yes, the "Y" was segregated at one time, even up in the North.)

- Getting the first black policeman hired on the White Plains police force.

- Getting the first black nurse hired at Grasslands Hospital in Valhalla, NY. (Now, the Westchester Medical Center.)

- Working to get decent, low-income housing built in White Plains in the late 1940's. It became known as the "Winbrook Housing Development" (a.k.a. "The Projects.")*

- Working on the National NAACP, and the National Urban League.

Recognition

Over the years, my father received several awards for his civil rights work.

In 1956, he received the City of White Plains' "Human Relations Award." (The first time a negro had received that award.) It was in recognition for his pioneering work in Civil Rights in White Plains and Westchester County.

In 1961, he received the "Rheingold Good Neighbor" Award. Again, for recognition for his Civil Rights work.

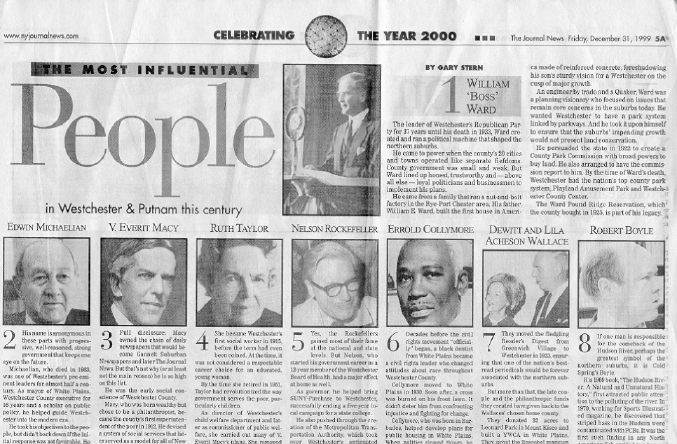

In 1999, he was honored, posthumously, with the recognition from the NY Journal News (a Gannet Newspaper) as one of "The Most Influential People of the Twentieth Century in Westchester and Putnam Counties." He was ranked at number six (right after Nelson Rockefeller, #5).

That article follows.

* Originally the White Plains "city fathers" had agreed to the location, cost, size and budget for the housing project. But then, they decided that they'd rather build a new post office on the site and postpone the building of the needed housing and relegate it to a less-desireable location. My father and other black leaders were outraged at this, and my father wrote a letter directly to then, President Harry Truman. President Truman wrote back and told the "city fathers" that he was directing them to keep to their original agreement. The housing project went ahead as originally planned.

Articles reprinted with permission from the N.Y Journal News www.nyjournalnews.com

Page updated on October 30, 2022 2:32 PM

Copyright © 2010, 2022 by James L. Collymore - All Rights Reserved